The SNP must rethink its economic model for an independent Scotland

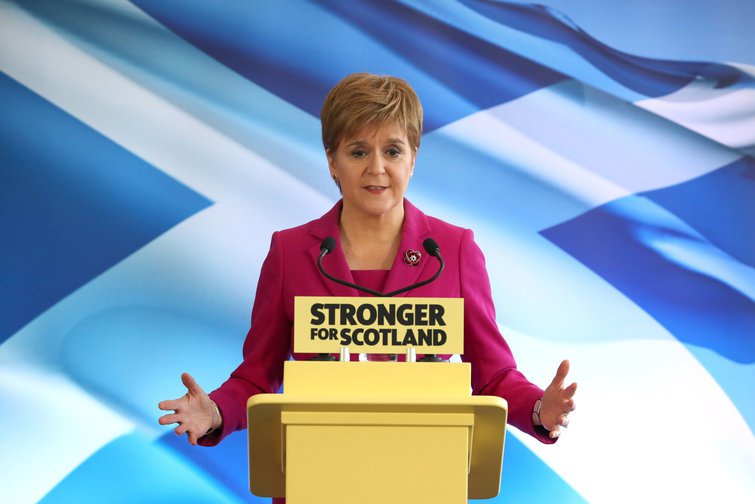

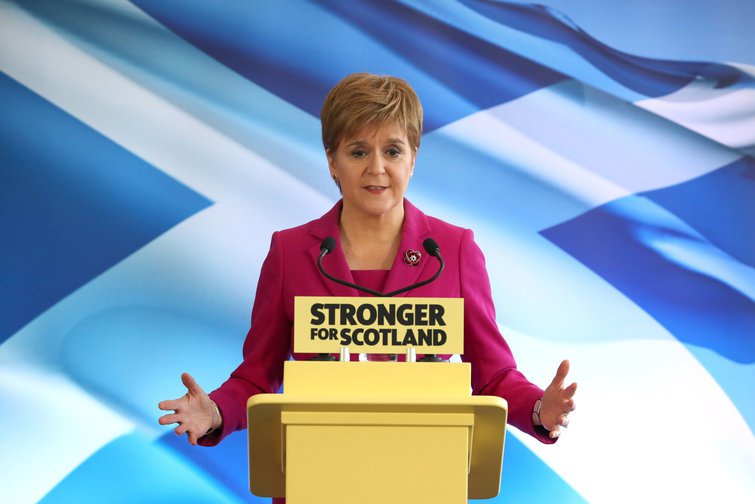

The blueprint commissioned by Nicola Sturgeon offers a future of less sovereignty – not more. It’s time to think again.

When a recent poll found support for Scottish independence had reached a record high of 58%, a wave of panic swept through Westminster. Senior Conservatives, anxious about the UK falling apart on their watch, responded by ordering the creation of a new government unit to “to turn the tide of Scottish nationalism”.

The fact that the poll arrived as such a shock indicates just how detached London has become from Scottish politics. Support for independence has been steadily increasing for some time, and for many the COVID-19 pandemic has only reinforced their doubts about being tied to the British state.

For those of us living in Scotland, COVID-19 has been a contrast of two governments. While the Scottish Government’s handling of the pandemic has been far from perfect, polls consistently show that a majority of Scots think Nicola Sturgeon has dealt with the pandemic more effectively than Boris Johnson. According to a recent YouGov survey, the first minister is not only more popular than the prime minister in Scotland – she is now more popular in England as well.

Set against the backdrop of a looming no-deal Brexit and Johnson’s bumbling premiership – neither of which command public support in Scotland – the gap in legitimacy between the leadership in Edinburgh and London has never been starker.

As Joyce McMillan puts it: “It’s not so much that the case for Scottish independence is being won in Edinburgh, as that the case for the Union is being lost in London.”

For the SNP, the hard-fought battle to convince a majority of the population that Scotland should become independent appears to have been won – for the time being at least. The main challenge now is practical: can Nicola Sturgeon’s party devise a credible plan for transitioning out of the UK and starting life as an independent country? Here, the picture is far less rosy.

The Sustainable Growth Commission

In 2014, the SNP set out the economic case for independence in the white paper, ‘Scotland’s Future’. The paper set out a vision of a fairer, more progressive and more democratic Scotland – a vision which inspired many to join the Yes campaign and champion the cause of independence. However, among its shortcomings were overoptimistic forecasts of oil revenues, and an assumption that the UK Government would agree to a currency union, neither of which materialised. These weaknesses were widely recognised as a key factor in the defeat of the Yes campaign.

In order to rectify these shortcomings, in 2016 Nicola Sturgeon established the Sustainable Growth Commission. Chaired by Andrew Wilson, a founding partner at influential public relations firm Charlotte Street Partners and former SNP MSP, the Commission was tasked with (among other things) making policy recommendations on “the range of transitional cost and benefits associated with independence”.

After long delays, the Commission published its final report in May 2018. At over 300 pages long, it was hailed by its authors as the most comprehensive and detailed plan for Scottish independence to date. But for those who actually read the report, it quickly became apparent that something had gone badly wrong.

A new country for whom?

The report begins by thanking the “wide range of interests” the Commission asked for ideas about how Scotland’s economic performance could be improved. Among those consulted, 17 out of 23 were business lobby groups, such as CBI Scotland, the Scottish Property Federation and the Institute of Directors. Notably absent from the list were trade unions, environmental groups, or any group representing workers or marginalised communities in Scotland.

Was this shunning of progressive voices a minor procedural glitch, or did it reveal the kind of economic model envisioned by the Commission? The proposals for putting Scotland’s public finances on a “sustainable and credible” path soon provided the answer.

Using the Scottish Government’s own figures as a starting point, the Commission recommended that Scotland should aim to reduce its fiscal deficit from a predicted 8.2% in 2021-22 to less than 3% of GDP within “five to ten years”. It also recommended Scotland’s national debt should be kept below 50% of GDP, and government borrowing should only be used to finance public investment.

In order to bring the deficit down, the Commission opted not for raising taxes – but suppressing government spending. It assumed that growth in public spending would be limited to 1% less than GDP growth for the first ten years.

Applying these rules retrospectively reveals why they are problematic. In 2019, GDP growth in Scotland was 0.7%. Under the Growth Commission rules, this would mean that public expenditure would have shrunk by 0.3%. In reality, public spending increased by 3% – under a fiscal framework overseen by a Tory treasury.

Applying the same assumptions going forward would see public spending as a proportion of GDP fall by around 4% over a decade. To put it another way: the Commission’s plan would see the size of the state in Scotland shrink at a faster pace than when George Osborne was chancellor. At a time when the world is turning its back on austerity, the Growth Commission seemed determined to bring it back to life.

Whether it was intentional or not, the underlying assumption of the Commission’s fiscal plan is clear: the transitional costs of becoming an independent country should be borne by those who rely most heavily on public services.

Back to the future

The narrow focus on fiscal discipline is not the only part of the Growth Commission’s report that feels like a discredited International Monetary Fund (IMF) document from the 1990s. Throughout the report there is a slavish adherence to a kind of economic orthodoxy that even institutions like the OECD and IMF have long since moved on from.

Rather than setting out a bold vision for Scotland’s economy by drawing on the latest economic thinking, the Commission attempts to identify “general themes that are observed consistently across high performing small advanced economies”. These themes are then used to identify an uninspiring list of key features that should underpin Scotland’s “next generation growth model”, such as being “innovation-focused”, “competitive”, “export-orientated” and having “flexible labour markets”.

To the extent that other modes of capitalism are explored, the analysis is rudimentary and superficial. The Nordic model is described as “attractive but challenging” because it “rests on a particular social model, a high and broadly-shared stock of human capital, and high levels of productivity”. It is ultimately ruled out as a viable option on the basis that “longer term improvements to Scotland’s productivity performance would be required to move towards such a model”. However, many of the key features of the Nordic model, such as high levels of taxation, widespread public ownership and strong collective bargaining, are glossed over or ignored – as is the fact that Scotland’s productivity today is far higher than it was in Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway when these countries first adopted the model.

Ireland’s tax haven model is also considered and ultimately ruled out, but only because “Ireland has strong first mover advantage, and Scotland has a challenging fiscal situation that would make it difficult to deliver aggressive tax cuts”. It isn’t difficult to detect where the authors’ ideological sympathies lie.

How Scotland’s economy will be transformed after independence, and in whose interests, is left unanswered.

By failing to interrogate how different economic models might contribute to different social, economic and environmental outcomes, the Commission’s recommended “growth model” ends up being little more than a list of lowest common denominators. How Scotland’s economy will be transformed after independence, and in whose interests, is left unanswered. Similarly, while challenges such as climate change and inequality are highlighted as problems that need to be addressed, there is scant detail on how the levers of independence should be deployed to tackle them.

Had the Commission bothered to tap into the wealth of talent and creative thinking across Scottish civil society, things might have been different. Rather than declaring that “an independent Scotland should be able to reap the long term benefits of oil revenues for many years to come”, they might have heard how a just transition away from fossil fuels is a better way to secure jobs and sustainable prosperity. Rather than ignoring the importance of care work to the functioning of modern economies, they might have heard how placing free, universal care at the heart of Scotland’s economic model would be both popular and good for the economy. Rather than fetishising GDP growth, they might have heard how prioritising alternative indicators of prosperity would be far more appropriate in the context of the challenges of the 21st century.

The 2014 referendum unleashed a wave of new thinking about the possibilities for the Scottish economy, which the Commission seems to have worked hard to ignore. If the aim was to inspire people that ‘another Scotland is possible’, it failed miserably.

A generous interpretation of the report is that its recommendations were designed to ensure that independence involved minimal changes to the present UK arrangements. But if that is the case, then what is the point of independence?

Currency chaos

Perhaps the most controversial area of the independence debate relates to currency. The Growth Commission recommended that an independent Scotland should initially retain pound sterling without any agreement with the UK government (an arrangement also known as ‘sterlingisation’). A new Scottish currency should be launched “in the long term” if – and only if – six stringent economic tests were met.

In a recent interview with The Herald, Andrew Wilson elaborated on this position, stating that rushing into a new currency “would be short-term risky, politically difficult, and it would make the cost of government borrowing more expensive... The monetary policy situation that we have now would continue until such a time that it’s no longer in our interests.”

It is here where the Growth Commission moves from being disappointing to being downright dangerous. While it is true that some countries use other currencies without the permission of its parent country (often the US dollar), these countries are typically smaller, less developed economies with far smaller financial sectors.

The claim that with sterlingisation “the monetary policy situation that we have now would continue” is either deliberately disingenuous, disturbingly ignorant – or both. Today Scotland benefits from being part of a monetarily sovereign nation state that issues a global reserve currency. Public spending is financed by HM Treasury and the Bank of England, some of which is allocated to the Scottish Government to spend on devolved matters. Scottish banks have access to Bank of England liquidity facilities, and in times of crisis economic harm is cushioned by the manipulation of interest rates, central bank interventions, fiscal transfers and currency revaluations.

The Scottish Government does not control these levers, but it does benefit from them (even if the UK government doesn’t always use them wisely). Under sterlingisation, these benefits would disappear: Scottish banks would no longer have access to Bank of England liquidity facilities, so could experience regular bank runs; monetary policy would be set in London by the Bank of England, who wouldn't take any consideration of Scotland’s economic circumstances; and fiscal policy would be constrained by the terms set by investors willing to lend sterling, most of whom would also be in London. If the point of independence is to gain more control over Scotland’s economy, this is a strange way of going about it.

For a sterlingisation regime to have the slightest chance of surviving, Scotland would also need to build up a vast stockpile of sterling reserves. Tens of billions would be needed to provide credibility to bond markets and ensure the banking system can function, and if the Scottish Government wanted to underwrite retail bank deposits (which are currently guaranteed up to £85,000 in the UK under the Financial Services Compensation Scheme) up to £120 billion would be needed.

There are only four ways that the Scottish Government would be able to obtain sterling. Firstly, it could spend less on public services than it raises in taxes (i.e. run a fiscal surplus), thereby obtaining sterling from the private sector. Secondly, it could ensure that more money flows into the country than leaves it, for example by exporting more than it imports (i.e. run a current account surplus), thereby obtaining sterling from abroad. Thirdly, Scotland could borrow sterling on financial markets by issuing sterling denominated bonds. Finally, the Scottish Government could sell assets (i.e. embark on a programme of privatisation) or secure aid or remittances from foreign entities.

Much of the debate on the economics of Scottish independence focuses on Scotland’s large fiscal deficit. While the exact size of Scotland’s fiscal deficit upon becoming an independent country is unknown (and inherently linked to policy choices), it is likely that turning this into a fiscal surplus would require painful spending cuts or tax rises. But the much bigger problem is Scotland’s other deficit – the current account deficit – which in recent years has been around 10% of GDP.

A current account deficit is not necessarily a problem for countries with their own currencies, but under sterlingisation the current account position becomes crucial. This is because it becomes a key determinant of the money supply. As the economists Angus Armstrong and David McCarthy put it, under sterlingisation “the balance of payments would become the key barometer of whether Scotland’s economy prospers or declines.”

Large public investment programmes would be relegated to a distant wish list

A current account deficit of 10% would mean that up to £16 billion would be draining out of the Scottish banking system overseas each year. Without access to the Bank of England to replace this, the Scottish Government would need to borrow sterling on international markets or sell public assets. This would be required simply to prevent the system from collapsing – borrowing to fund the fiscal deficit and pay for public services would be additional to this. Large public investment programmes would be relegated to a distant wish list.

Ultimately, a country trying to fund large twin deficits by borrowing extensively in a foreign currency would only survive for so long. Financial markets would see the writing on the wall, and demand ever higher interest rates on Scottish debt. It would likely only be a matter of time before Scotland’s public finances became unsustainable, the sterlingisation regime collapsed, and a new Scottish currency was launched out of necessity.

For this to happen in a chaotic uncontrolled manner would be disastrous – both for the Scottish Government, which would lose all its foreign exchange reserves and much of its international credibility, and for households and businesses, who would bear the brunt of a painful adjustment.

Given this, it is unsurprising that few – if any – credible economists share the Growth Commission’s enthusiasm for sterlingisation. Even Richard Marsh, an economist who provided advice to the Growth Commission, recently wrote that “No credible economist would advocate sterlingisation as the policy of choice for an independent Scotland.”

In a revealing exchange with then finance minister Derek Mackay that was recently published under the freedom information act, an unnamed economist – rumoured to be a high-profile academic that serves on a number of the Scottish Government advisory bodies – wrote that:

“I was very disappointed with the Growth Commission report, as I believe most people who have read it are… You were badly let down by the authors of that report and I am surprised that you and your other colleagues on the Commission accepted such a poor piece of work.”

For the time being however, the public don’t agree. Polling shows that keeping the pound remains the most popular currency choice among Scots, while establishing a Scottish currency has precious little public support. If SNP leadership wants to make a success of independence, it would be well advised to start shaping public opinion on currency options – and stop following it.

Scottish dependence

The Growth Commission proposals were problematic enough when they were published back in 2018. But as many of us warned at the time, the biggest problems would arise when an economic crisis hit. We didn’t have to wait long to see what such a crisis might look like.

In the unlikely event that an independent Scotland did survive its first few years under sterlingisation, it would almost certainly not survive contact with COVID-19. Across the world central banks have intervened on an unprecedented scale to support government spending on public health and income support schemes, either by monetising deficits directly or by intervening in bond markets to keep interest rates low.

Without a central bank to accommodate such a fiscal expansion, a sterlingised Scotland would have been entirely reliant on international investors willing to lend sterling. The absence of a lender of last resort would mean paying higher rates of interest on Scottish sterling bonds, and tailoring public policy to look ‘credible’ to financial markets. It would also leave Scotland vulnerable to predatory investors looking for vulnerable prey to exploit during a crisis.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that the UK’s fiscal deficit will increase to 16% of GDP this year due to COVID-19 spending. For Scotland, the IFS predicts that the equivalent figure could be as high as 28%. Were a sterlingised Scotland to attempt to borrow from financial markets on anything like this scale, it would most likely lead to a vicious cycle of rising borrowing costs and deteriorating budget deficits, as higher interest payments led to a worsening budget position, which in turn led to credit rating downgrades and higher borrowing costs, eventually requiring steep cuts to public expenditure and asset sales. This would be combined with a heightened risk of a financial crisis, as Scottish banks struggled to obtain the sterling needed to maintain functioning of the banking system. During a global pandemic, such a course of events would be literally lethal.

Without having recourse to traditional macroeconomic levers to get the economy back on track, the only option would be to go cap in hand to the IMF. Once again, the inevitable result would be the abandonment of sterlingisation and the establishment of a new Scottish currency – albeit under desperate conditions.

a future of less sovereignty, not more

There are some who say that none of this matters, because these are all issues that can be resolved after Scotland becomes independent. But the initial decision taken on macroeconomic arrangements creates a path dependency which makes it extremely difficult to change course without a painful adjustment. The reality is that the Growth Commission’s plan for sterlingisation would lock Scotland into an economic straitjacket from which it may never escape.

Despite being a blueprint for independence, in reality the Growth Commission is a plan for greater dependence – on the City of London, international capital and predatory investors. It offers a future of less sovereignty, not more.

Many in the Yes movement support independence because they believe it offers a path towards a more progressive future. But the vision outlined in the Growth Commission delivers the opposite: it is difficult to conceive of an economic settlement better designed to ensure that government policy serves the interests of international finance rather than its own citizens.

Back to the drawing board

The Growth Commission has not escaped criticism from within the SNP ranks. At the party’s 2019 spring conference, members successfully amended the leadership’s motion to endorse the Growth Commission’s currency recommendations by voting through an amendment calling for a new currency to be established “as soon as practicable after independence day”. While this offered some consolation to disgruntled members, in practice such a vague pledge does little to tie the hands of the leadership. At the party's 2020 conference next month, activists hope to land another blow to the Growth Commission plans by putting forward a motion calling for the establishment of a Scottish central bank within a committed time frame. Whether this will be successful remains to be seen.

With the SNP on track to win a majority at next year’s Holyrood elections, another referendum on independence looks increasingly likely. And with little sign that work is underway on a replacement to the Growth Commission, it remains possible that its flawed proposals will form the basis of the official independence campaign.

For those who support independence, this should be alarming. In 2014, the pro-UK parties entered the referendum campaign with a commanding lead in the polls. But overconfidence, a lacklustre campaign and lack of a compelling vision meant that Scots came very close to voting for independence. This time around, the fatal flaws in the Growth Commission’s proposals means it’s possible the reverse could happen.

None of this is to say that Scotland cannot flourish as an independent country. With the right plan on currency, economic model and transition, there is no reason why Scotland could not become a successful independent nation. But that plan needs to come from the 2020s, not the 1990s. And it needs to come from a broad cross section of civil society, not just business groups.

Far from being an asset to the independence cause, the Growth Commission is its biggest liability. It’s time, as we say, ‘tae think again’.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.